(Editor’s note: This piece was generously contributed by visiting researcher and graduate student Jeffrey D. Broxmeyer of City University of New York, who used the Southwest Collection’s Tweed Family Papers as research material for his dissertation.)

William M. Tweed played a leading role in one of the great dramas of the postbellum period, the New York “Tweed Ring.” The group was composed of Tweed (Grand Sachem of Tammany Hall, state senator, and city Commissioner of Public Works), Oakey Hall (mayor), Richard Connolly (comptroller), and Peter Sweeny (district attorney), as well as a colorful cast of lesser politicos, contractors, and hangers-on. Historians estimate that between the late 1860s and early 1870s the Tweed Ring defrauded the City of New York from anywhere between $50 million (or $940 million today) and $100 million ($1.8 billion). Most of the money was never recovered.

The collapse of the Tweed Ring led to political crisis in New York and across the country. Considering the Ring’s breathtaking scale of operations, the scandal touched nearly the entire New York political class. One clipping I found in the Southwest Collection’s Tweed Family Papers came from the New York Herald, and was dated November 14, 1878. It quoted Senator Booth, a Republican, claiming that the taint of scandal directly touched “hundreds, both democrats and republicans, not only in the city of New York, but throughout the state.” With Tweed’s erstwhile ally turned prosecutor, Samuel Tilden, running for president, the Ring also became a major national issue during the contentious Election of 1876.

But how did Tweed generate his vast personal fortune? Reformers, journalists, and historians have often assumed that Tweed simply embezzled his fortune directly from city funds. This characterization, however, does not do justice to the complexity of Tweed’s operations. At the outbreak of the Civil War, bankruptcy records show that Tweed’s modest chairmaking shop, William M. Tweed & Brother, was significantly in debt. According to his later confession, at his pinnacle Tweed’s net worth was at least $6 million (or $113 million today). My research suggests that in fact much of Tweed’s personal wealth came not directly from embezzled funds but through his extensive and diversified business portfolio. During the height of Gilded Age boom times, Tweed leveraged his political influence toward speculative investments in banks, railroads, mines, newspapers, transportation, and real estate. Tweed’s real estate activity was particularly impressive, and he bought and sold valuable plots of land all over Manhattan to everyone from small-time Tammany hacks to the Astor family. Tweed even incorporated his own steamship company to ferry elite New Yorkers from Manhattan to their vacation homes in Greenwich, Connecticut.

It was, however, a short-lived business empire, as the Tweed Family Papers, collected by William’s sister-in-law, Margaret, illustrate. William was close with his brother Richard’s family, and the papers document the extreme financial hardship they all experienced in the wake of the scandal.

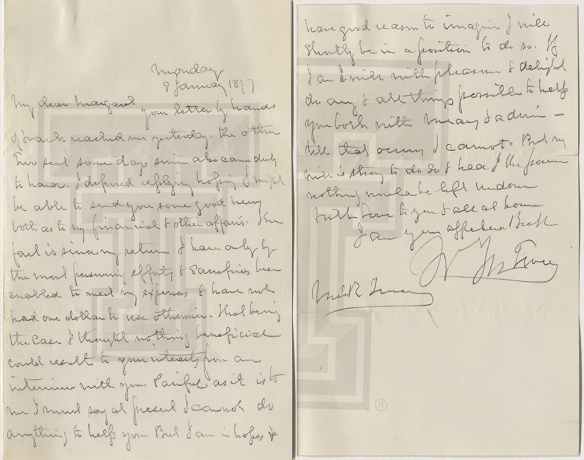

William was first arrested in 1871. The Southwest Collection’s archives suggest that after six years of costly legal battles, his wealth was exhausted. Correspondence shows that, even with “the strictest economy,” his sister-in-law Margaret was desperate to avert foreclosure on their home at 339 W. 57th Street. Despite months of her pleadings, William lamented that he was in no position to help. On January 8, 1877, William candidly explained his own predicament in the letter above: “The fact is since my return [to jail] I have only by the most pressing efforts and sacrifices been enabled to meet my expenses. I have not had one dollar to use otherwise…Painful as it is to me I must say at present I cannot do anything to help you. But I am in hopes to have good reason to imagine I will shortly be in a position to do so.”

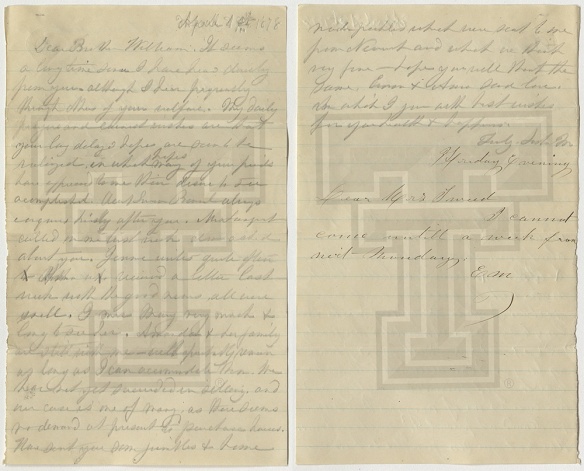

Months later, William replied once again to Margaret’s plea for assistance. Although she owed significant debts, she asked only for $97 to pay for heating coal during the winter. “My Dear Sister Margaret,” he wrote from jail on November 3, 1877 (above), “I am really sorry. I am so unfortunately situated…at the present time it is almost impossible to get the money I need from day to day. If I can help I will do so and with pleasure.” Margaret attempted to contact William one last time via the letter at the top of this article, written on April 4, 1878 only days before his death from illness in prison. “Dear Brother William,” she wrote, “my daily prayers…are that your long delay of hopes are soon to be realized.” These letters paint quite a different picture of William Tweed than those by Thomas Nast, the gifted Harper’s Weekly artist who created the iconic caricatures that helped topple the Ring. In his correspondence with Margaret, William appears a devoted and even humble family man; hardly the rapacious beast portrayed by Nast and others.

Years after the death of William, Margaret, and Richard Tweed continued to be plagued by financial duress. One of Margaret’s sons, Frank, wrote her the letter above on February 9, 1881, to explain why, with all manner of excuses, he could not send her money to pay rent. Another of Margaret’s sons, Alfred, frequently sent small remittances back east from Colorado, where he moved to escape the family legacy. But the scandal haunted him there, too. In the letter below from Denver and dated September 24, 1876, Alfred confessed to his mother than he had not succeeded in making a “quick fortune” out West. The Tweed Papers show that only a few years earlier, Alfred had toured Europe and lodged in luxury hotels. Now, things in Colorado appeared to be going less well. “I have a slandered name and reputation here,” he reported. “The Boss if all be true comes in for a due share of bad luck. And we all as a family seem to be d–n unlucky.”

By Jeffrey D. Broxmeyer

Additional Locations for Archival Material Related to William “Boss” Tweed:

Columbia University Rare Book and Manuscript Library:

Edwin Patrick Kilroe Collection

John T. Hoffman Papers

New-York Historical Society Library:

Richard Connolly Papers

Charles S. Fairchild Papers

William M. Tweed Miscellaneous Manuscripts

New York Public Library:

A. H. Green Papers

A. Oakey Hall Miscellaneous Manuscripts

George Jones Papers

Samuel J. Tilden Papers

New York State Public Library:

Jay Gould Family Papers

Syracuse University Library:

Jay Gould Letters

Thomas Nast Collection

Tammany Collection, State Library, Albany, New York

Pingback: What’s New at the Southwest Collection? | Southwest Collection Archive